This Was the Most Beautiful Staircase in Paris

Plus, the horror of modern hotel bathroom design.

Feeling winded while scaling the steps of Sacré-Cœur is a common enough affliction, but there is one dignified way to catch your breath. Pause on the Rue du Cardinal Dubois and wheeze out to your friends that you want to catch a glimpse of one of Paris’ lost treasures.

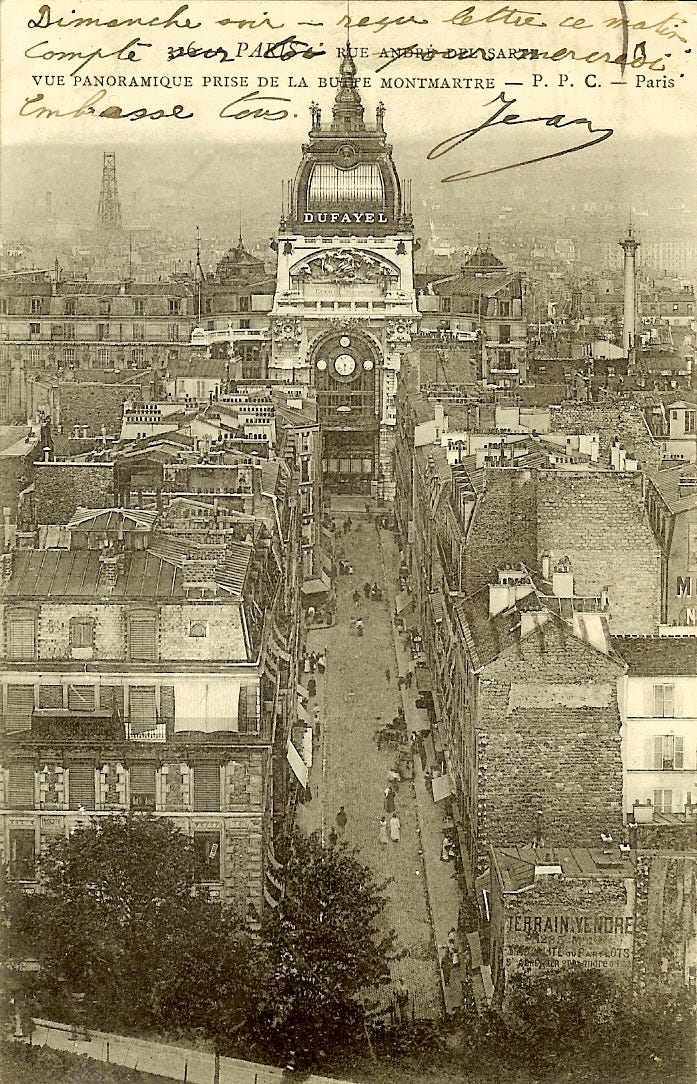

Turn to the right, and peeking above the tree and roofline is a hulking and ornate curved pediment. There’s something bleak about it—even just a glance will leave you feeling like it’s been shorn of something. On your descent from Sacré-Cœur, come back and follow the street to the steps down the side of the hill to the Rue Andre del Sarte. On the way, you’ll catch further visions of this strange building, with elaborate sculptures and stonework that frame rows of tiny modern office windows huddling in its shadows, as if they, rightfully, are embarrassed to be there.

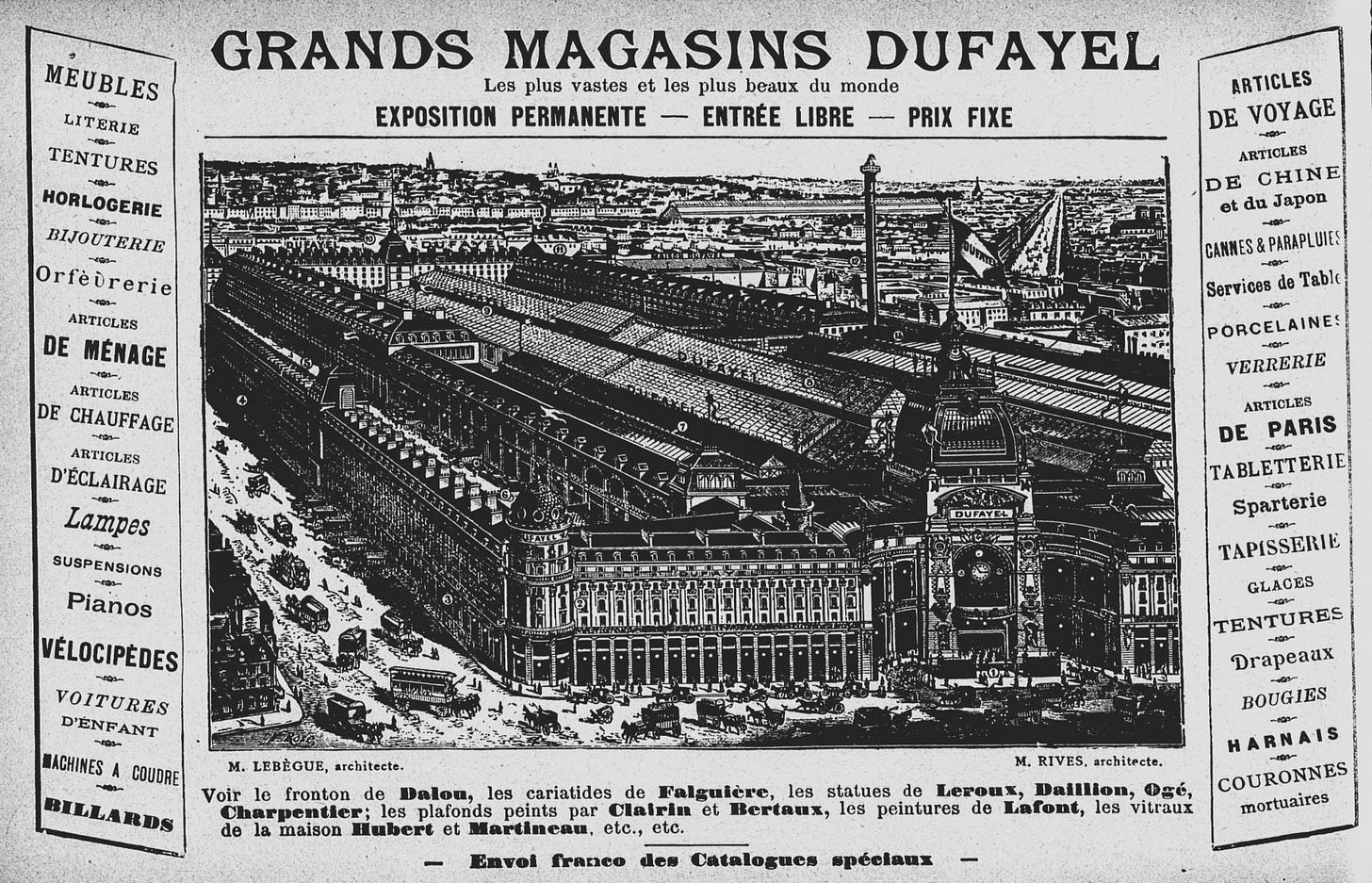

This Frankenstein edifice at 26 Rue de Clignancourt is all that remains of the grand entrance to what was once the largest department store in the world, Les Grands Magasins Dufayel. Its ornate halls took up nearly an entire city block in the 18th arrondissement.

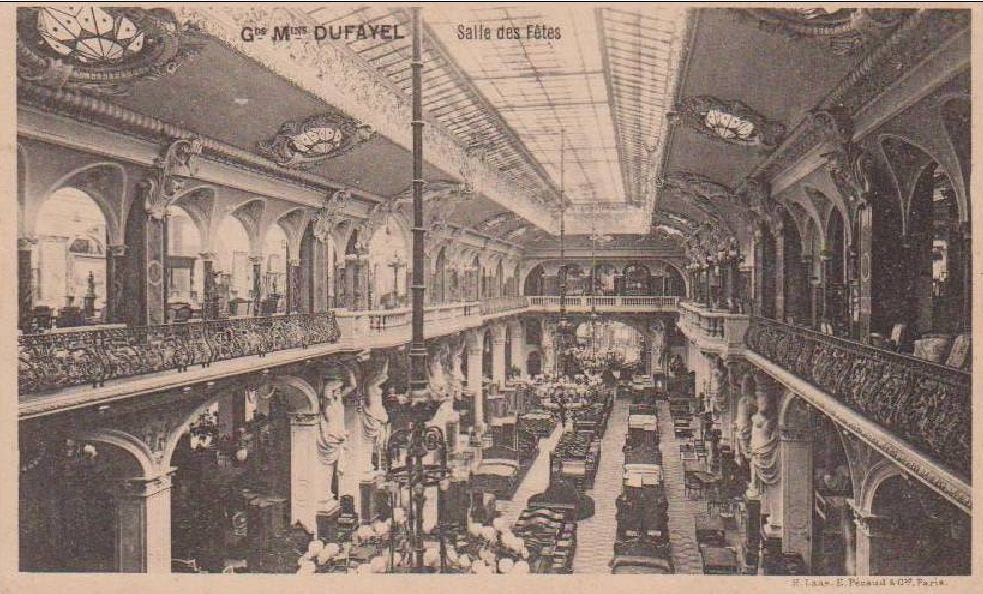

Designed by the most over-the-top of turn-of-the-century architects, George Rives, it had a winter garden, a towering steel dome, a 112-foot theater, and a main shopping hall made up of marble columns and a glass ceiling lit by 3,000 electric lamps.

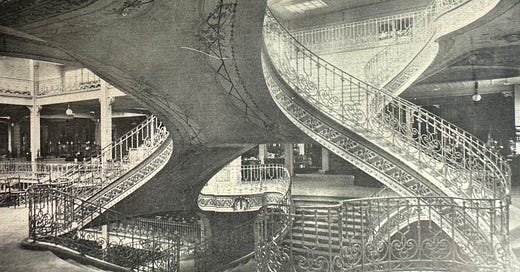

Despite all the opulence (“decorated with a luxury that borders on profusion,” opined Architectural Record) it was a four-branched staircase that captivated the design world then and which drew me into this whole saga.

Strangely enough, all this opulence wasn’t for the nouveau riche of Paris. Instead, Les Grands Magasins Dufayel was unabashedly a store for the working class, which often made it a target of derision for snobs. “To the masses,” wrote a sneering French critic, “this colossal boutique seems like a fairy-tale palace.”

The neighborhood of Goutte d’Or stretches roughly from the eastern side of the butte Montmartre to the blocks surrounding the railway lines of the Gare du Nord. Its streets have been populated by the working class for centuries. In the 19th century it was filled with workshops, factories, and migrants coming off the trains looking for work. Starting in the 20th century it became the area where many immigrants from North and Sub-Saharan Africa settled. Largely untouched by Haussmann, it was also left without public spaces where the working class could spend leisure time. Left with nowhere else to go, they filled its bars to such an extent that Emile Zola set his iconic novel L'Assommoir on poverty and alcoholism here.

Dufayel’s became their “third place.” It was founded by Jacques François Crespin 1856, who found success hawking photographs on credit to the neighborhood’s workers. He opened a store called Le Grand Magasin des Nouveautés. When he died in 1888, one of its employees, Georges Dufayel bought it and renamed it after himself. The grand store became famous first and foremost because of how it made lots and lots of cash. According to reports, by 1902 the store was pulling in $26,000,000 a year in revenue. The biggest moneymaker was in lending “credit notes” to customers that could be redeemed at hundreds of shops throughout Paris, making it one of the first large-scale promoters of consumer credit. These shopping loans were then collected by the 800 cashiers working for Dufayel, and despite the poorer backgrounds of his customers, delinquencies were so few that all his legal work was handled by a grand total of four clerks.

The second reason it was famous was that towering over its entrance was a 30-meter dome of glass and steel and on top of that dome was a searchlight.

“Two powerful searchlights can be seen from all quarters of Paris every night,” wrote one newspaper account from 1902. “One is that of the Eiffel Tower and the other, which is almost as powerful, is that of Dufayel’s store,” powerful enough to pierce the night sky for several kilometers.

The third draw was that much of what actually went on at Dufayel wasn't directly related to shopping. There was a winter garden, a palmarium, daily concerts, massive theater, invention showcases, and a free cinema that would arguably alter cinematic history. Families would often come just to picnic here.

Jean Renoir, the son of the Impressionist Pierre-Auguste Renoir, was one of the giants of film from the 1930s through the 1960s. (His obituary written by Orson Welles is a taste of the esteem with which directors held him and his work.) It was at Dufayel that Renoir first fell in love with film. In his memoir, he recounted that at “the entrance to the store a man wearing a braided cap asked us if we wanted to see the cinema … Scarcely had we taken our seats than the room was plunged in darkness. A terrifying machine shot out a fearsome beam of light piercing the obscurity, and a series of incomprehensible pictures appeared on the screen, accompanied by the sound of a piano at one end and at the other end a sort of hammering that came from the machine.”

Dufayel’s cinema was free and considered a technological marvel for its ability to perform sounds that imitated the sounds of water, the steps of men and horses, guns, and cannons.

It was here at Dufayel that the films of Georges Méliès (of The Invention of Hugo Cabret fame) were screened. This was important as an essential part of the “rediscovery” of Méliès involved finding hundreds of reels of his films shown at Dufayel in a shed at the country house of Rives!

The fourth and final draw was the building itself, for which no expense was spared. Taking up nearly 19,000 meters, it was an ostentatious display of Belle Epoque excess, yet it was all built in 18 months. Dufayel used the king of “opulent eclecticism” to design it, Gustave Rives. If you are walking around Paris and happen to stumble on a hefty building whose decorations are slightly out of whack with those around it, there’s a fair chance Rives designed it. Which is ironic given his mentor was the paragon of classical restraint and rationalism, Eugene Train. I like to think of Rives as sort of the Trumbauer of France.

Renoir wrote about the experience of entering Dufayel, exclaiming, “"The building, with its walls of real stone and large glass windows shedding their light on imitation Henri II sideboards, gave to those privileged to enter that temple of mass-produced goods an impression of solidity capable of withstanding anything.”

Many of the illustrations published by Dufayel to promote the grand magasin were exaggerations showing it stretching for hundreds and hundreds of meters, but it was still an impressive complex taking up nearly an entire block. And while nothing except the riveted iron framework remains inside, you can trace much of it from the outside today. Often because Rives had his name carved on every corner. Much of the ornamentation has been stripped, and most of the retail is pretty sad. There is graffiti, and the modern materials used throughout are shabby.

Dufayel died in 1916 and the store closed in 1930 after the stock market crash. Many of the grand department stores—Printemps, Bon Marche, Galeries Lafayette, Samaritaine—still stand and are worth visiting. But the sad remains of Dufayel are a reminder of how the tail end of the Gilded Age must have been wild with how swiftly things became outdated and anachronistic—means of transport, borders, dress, music, marriage, communication, art, and architecture. And once something was outdated, it was quickly torn down or left behind.

After closing in the 1930s, the store was used for soldiers during the war and in 1951 purchased by BNP Paribas. Soon after, its famed tower and beacon were torn down. BNP clearly felt no attachment to it—the grand clock and glasswork at the entrance were replaced by those sheepish rows of small windows. Domes on the corners were lopped off. The grand staircase torn out. The complex was broken up.

BNP finally sold the entrance a couple years ago to the VINCI Immobilier group. It is currently turning it into offices that in a very cringe contemporary French fashion are being called “WOW.” Where the glass dome used to stand will now be a rooftop terrace for workers. When I last visited in September, the sad rows of windows were being replaced entirely by glass, which I’m not sure is an improvement but neither is it worse.

But every time I see a photo of that staircase, I catch my breath. Maybe somebody will attempt to rebuild them someday.

DEPARTMENT OF GRIEVANCES

New York City passed legislation this week further tightening its rules on the hospitality industry. Whereas previous laws attacked the short-term rental market (an attack the hotel industry supported), the city council is now going after hotels. Among the provisos are requirements that hotels provide 24/7 staffing or security, daily room cleaning unless a customer declines (but the hotel can’t incentivize them doing so), no bookings for less than four hours, and all employees must be hired directly by the hotel. I understand where a lot of this is coming from—safety concerns, wanting to combat models like Sonder, and boosting hotel worker unions. But it seems to me that yet again all this will do is raise hotel prices and further hurt New York City’s sluggish post-COVID recovery. After all, the city still hasn’t reached 2019 numbers in terms of visitors, and doesn’t expect to until next year. Meanwhile, the city still has done nothing to get rid of its universally reviled resort/destination fee nonsense. That would make me much happier.

When it comes to popular Instagrammable sights that have already been trammeled by overtourism in a way that cannot be undone, European authorities should charge ridiculous ticket fees for non-locals and non-students. Americans have money to spend and if people want to see the Via dell'Amore in Cinqueterre or make a day trip to Capri, they’ll pay $20 or $30 no problem. After all, a museum visit in the U.S. costs at least that. Venice seems to be taking note. It is now doubling the day-tripper fee to 10 euros from 5 euros. (Although if you book in advance you can still pay the lower 5.) The fee will only apply from April 18 through July 27 to those visiting for the day on Friday through Sunday and holidays from 8.30 a.m. to 4 p.m. I think they should go for it fully and charge more and have it in place six days a week.

And now France is considering charging tourists an entry fee for Notre Dame (previously there was only a fee to go to the top. For what it’s worth, the church is state-owned).

Again, though, this should be targeted at deep-pocketed foreigners and not locals or young people, as doing so can cause domestic tourism to become too expensive. The Telegraph had a nice write-up this week of the ways in which all these increasing fees can make enjoying one’s own hometown prohibitively pricey. Which is why I was happy to see the Whitney in New York City announce it will be free to all visitors under the age of 25 starting in December.

The new refund rule from the Department of Transportation goes into effect tomorrow, which clarifies and strengthens passenger rights when their flight has been canceled, significantly delayed, or impacted. A good rundown of what exactly you can expect can be found here.

A little over two years ago, I ran a piece at The Daily Beast titled: “Why Greenland Is Now So Much Cooler Than Iceland.” While I’d anecdotally heard people talking about Greenland the way I’d once heard them talk about Iceland, it wasn’t until Tim Johnson pitched that framework that it all clicked. Over the last year, however, I’ve seen more and more of the types of travelers who aren’t exactly edgy heading to Greenland. It has become, in the words of the Wall Street Journal this week, “brag-worthy.” And the chance to be one of the Americans who experiences it before it becomes overrun with other Americans has turned into the tourism equivalent of a gold rush. Everybody going there now wants to see it before their countrymen (with the same motivations), ruin it. Flights, for instance, will double next year, with United adding seasonal service.

The horror of modern hotel bathroom design—barn or glass doors, for instance—is no doubt familiar to many of you. And inexplicable. But Andrea Sachs at the Washington Post investigated what, exactly, is going on with hotels making these loathsome design choices.

I dislike doing restaurant research, and find many of the online resources irrelevant to my needs and tastes. The one exception is Eater, which I will sometimes use as a starting point. So I’m glad to see the website has launched an app with its handy maps!

INDUSTRY NEWS

Six Senses to open hotels in Milan and Lake Como

Canadian French has been added to Google Translate

Air taxi startup Lilium is out of cash and headed to insolvency

Malaga is banning short term rentals in a number of neighborhoods

Elliott Management drops Southwest proxy challenge

The Vessel at Hudson Yards reopened

The New York Times ate at every Carbone in America

State Department issues terrorism warning for popular surf spot

This is the least-used train station in the U.S.